In 1997, when Fred Rogers (Mr. Rogers) received an Emmy Award for his Lifetime Achievement in children’s television, his acceptance speech famously included an exercise, during which he invited audience members to spend just 10 seconds calling to mind people who had made a difference in their lives, who had helped them become who they are. Reportedly, that short reflection proved marvelously rich for those in attendance, many of whom were left misty-eyed by the experience.

While I wasn’t present for that award ceremony, I have viewed the video capturing that special moment multiple times, and it easily brings me to tears as well. When I take the time, even just the recommended 10 seconds, my mind can easily summon the faces of many good people, “icons,” if you will, of hope and encouragement, who have aided me along life’s path. Some are faces I would fully expect — family members, close friends, etc. — but others are faces of people whose lives only intersected with mine for a short period of time, yet their influence undeniably remains.

In the spirit of Mr. Rogers’ exercise, please allow me to introduce three such people, who have helped to make me the person I am today.

—

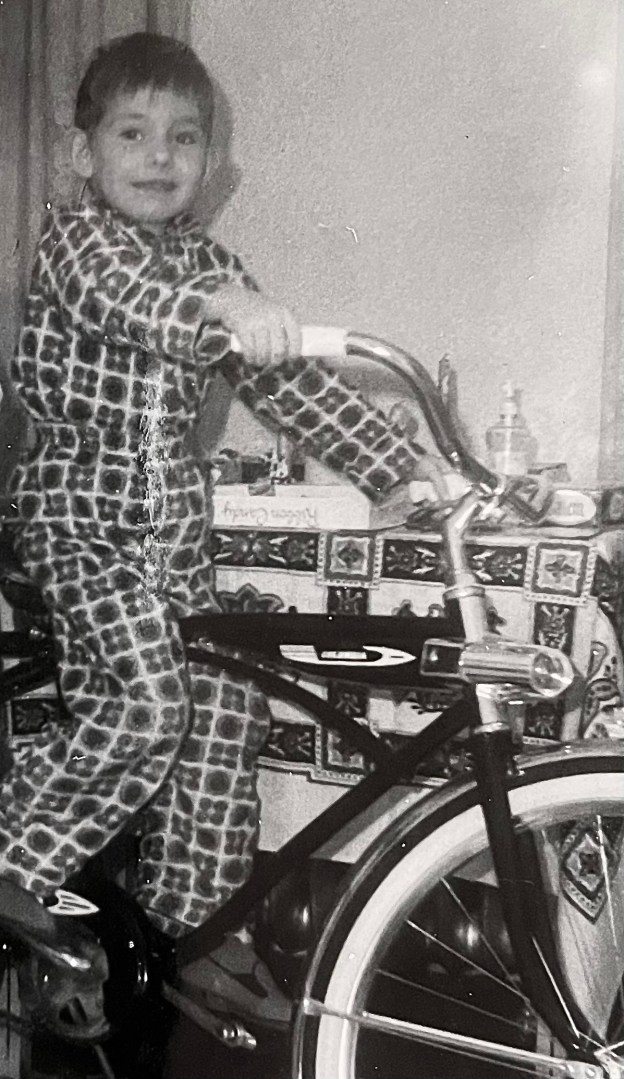

Jimmy, the Ice Cream Man

When I think of Jimmy, even after these many years, my heart smiles. He is someone from my childhood, who I knew virtually nothing about, except for the fact that his truck would turn the corner onto our street at roughly the same time every summer evening. He would then sound his familiar bell while pulling over to the right side of the road. The children of our neighborhood, myself included, would always be ready for him, clutching the coins our parents had given us, watching and listening together.

Jimmy was a heavy-set man, who moved slowly within the tight confines of his mobile ice cream shop. He was never unfriendly, but he spoke sparingly to his young customers, often soliciting each next order by a quick nod of the head.

He had an olive complexion, thick hands, slightly bulging eyes, and a round face that toggled between a smile and a smirk — a face that remains vividly accessible to me even today.

Yes, Jimmy served us creamsicles, strawberry shortcakes, fudge pops, and a variety of Italian ices, but those were not his only wares. Perhaps unbeknownst to him, Jimmy also served us innocent fun on a stick or in a cup. He served us a predictable rhythm in our young lives, an experience of shared expectation and joy. He brought us together on a common quest and helped to shape those blessedly simple summer evenings that bonded us in friendship.

Though Jimmy visited our neighborhood for the final time decades ago, he often still turns that corner and rings his bell in my cherished memories.

—-

Sister Mary Ann Follmar

“Follmar anxiety” cannot be found in the DSM-5, but it felt very real to my friend Liz and me when we were graduate students together in Sr. Mary Ann Follmar’s classes at Providence College. The faux ailment was a comical label Liz and I attached to our stressed-out frame(s) of mind when charged with writing research papers for our remarkable professor.

Holiness is not a measurable commodity, but when one is in the presence of a truly holy person, it is certainly discernible. I’m not referring here to an aura that sometimes accompanies celebrity. Instead, I’m speaking about an otherworldly quality that can be difficult to describe.

Christian theology asserts that God is holiness itself. In this view, God is perfectly pure and thus separated from all that is sinful. For a person to be holy, therefore, is for that person to manifest God-like qualities, i.e., to be similarly — though imperfectly — separated from sinfulness. I believe this quality of separateness is what people intuit when in the presence of a holy person.

Sr. Mary Ann exhibited such separateness, perhaps more strongly than anyone else I have ever encountered; however, rather than making her seem distant or unreal, the separateness manifested as deep joy and peace and thus acted as a powerfully attractive force. It was not unusual, for example, to find students gathered around Sr. Mary Ann at her desk before or after a class or even in the dining hall. She was also known to invite groups of students to her apartment for prayer, and many enthusiastically accepted.

Though known as Sister Mary Ann, she was not a nun; rather, she was a consecrated virgin in the Dominican tradition, who lived alone and spent several hours each day in Eucharistic adoration. The fruit of her devotion was powerfully evident.

Though she had no immediate family of her own in Providence, she took absolute delight in children, including our first child, Rachel, who was only four months old when I started my degree program. Sr. Mary Ann would positively beam in Rachel’s presence and was always eager to hold her, even if Rachel was having a fussy episode.

When my sister Christine passed away early in the spring semester of 1985, Sr. Mary Ann traveled with another of my professors, Fr. Giles Dimock, O.P., from Rhode Island to our hometown just outside of Boston for Christine’s funeral. Her (and Fr. Giles’) presence and support at that acutely vulnerable time meant a very great deal to me.

Sr. Mary Ann’s influence, in the classroom and (especially) through the witness of her beautiful life, made holiness seem possible for her students, including me. I doubt that spirituality would hold the same treasured place in my life if not for her. I will be forever grateful.

—-

Theodore “Ted” Vrettos

Ted Vrettos had a “yes” face that could easily transition into a mischievous grin. His laid-back classroom style put his students at ease and helped create a safe forum for creative expression.

I first met Ted when I enrolled in his basic Creative Writing class at Salem State College in the late 1970s. I had no idea at the time how much richer my life would be because of that encounter.

An endearing man, Ted was about 60 years old and an accomplished writer when I became his student. Thinking back, I struggle to recall anything that Ted actually taught me about the craft of creative writing. He did, however, do two things that I consider far more important. He encouraged my discipline as a writer, at least for as long as I was in his classes; and, he helped me to find and shape my writer’s voice.

I believe I took three classes in all with Ted and then finished up by participating in his summer writer’s conference in 1980. Beginning with my second class and continuing right through the writer’s conference, I was part of a committed group of Ted’s students, who took creative writing seriously and became very good friends. Four of them remain my close friends today, some 45+ years later. And, most of us continue to write.

In Ted’s classes, the desks in the room were always arranged in a circle. Ted would enter with his briefcase and assume his place at one of the desks in the front of the class. If he had given an assignment, he would begin there, but most of the time he would simply invite anyone with a newly written piece to read it aloud so that he and the class could critique it. The experience could be exhilarating, unnerving, even embarrassing, but we willingly subjected ourselves to the process because our desire was so strong.

A couple of years after graduation, someone from our group had the idea that we should get together again informally with Ted. My wife and I offered to host, and I reached out to Ted to see if he would consider joining us. He quickly agreed to come and asked if his wife Vas could also join in. In preparation, several of us, including me, wrote new stories to read to the group.

When the night came, we broke bread together, socialized for a while, and then fell back into our familiar pattern of sharing and critiquing. It was wonderful.

I saw Ted two more times in the early 1990s. First, I dropped by his house to invite him to come and speak at a Library Week program that would take place in the public library where I began my career. He was warm and welcoming as usual, and Vas prepared me a delicious lunch. He also agreed to come.

Our final encounter was a few weeks later at our Library Week program. Ted shared about his published books on the topic of Lord Elgin and his controversial removal of the Parthenon Marbles in the early years of the 19th century. He spoke eloquently, and the audience was very engaged. So, I was delighted with the program; but, I was sad to see it end. I sensed that my old mentor and I might never cross paths again after that night. That proved to be the case.

—-

At the end of December, I will be retiring from Boston College. It was not an easy decision because I genuinely love my job. Still, it’s time.

Being both naturally introspective and quite sentimental, I find myself in a reminiscing mood as the final days of my career tick by. Curiously, I’m not thinking at all about achievements through the years. They may have once been quite important, but their significance fades with time. Instead, my mind is occupied by the wonderful people I’ve been blessed to meet, work with, and serve during my career. It’s really all about them… and you.

“Jimmy, the ice cream man,” Sr. Mary Ann Follmar, and Ted Vrettos are all gone today.

I wish I’d had a final chance to say, “good-bye,” and to tell them how important they were (and are) to me.

I wish I had let them know that I love them.

—-

If you have been a part of my life, my work, or both, whenever I reserve 10 seconds (or more) to consider my helpers, your face may come to mind as one of my “icons.” Thank you!

And, just so you know, I love you too!