And the man and his wife were both naked, and were not ashamed. (Gen 2:25)

If an afterlife affords us the chance to pose questions to the Almighty, I’ll have (at least) one at the ready. “Why are so many people – okay, okay, why was I – so prone to shame during my life?” And, if allowed a follow-up, “Why do so many of us – or, why did I – allow shame to wield such stifling power?”

—

My cousin Michael came to mind unexpectedly one day toward summer’s end. I was instantly awash in fond recollections but soon found myself shaking my head with the realization that he and I hadn’t seen one another in nearly 30 years.

Once, we’d been quite close. From boyhood into early adolescence, a trusted hallmark of summer was Michael’s annual two-week (sometimes longer) stay at my first family’s home. He was two years older than I; and, during those visits, I always felt as though I suddenly had a big brother watching out for me, guiding me.

Michael and I never had a falling out. As we grew older, our lives simply went in different directions, and we gradually lost contact. My only adult encounter with him was at our mutual uncle’s funeral in the mid-1990s. Unfortunately, that brief but warm reunion never led to further contact.

With my curiosity piqued on that late summer day, I searched for Michael online. To my surprise, one of the top Google results turned out to be his obituary. I discovered that he had passed away on January 1st of this year after what was described as a “hard fought battle with cancer.”

The happy memories that had rushed to mind just moments before were all now tinged with sadness.

Then, I thought about short pants.

—–

Michael’s final stay at our house was during the summer of 1971. I was thirteen years old and he was nearly sixteen. Since the previous summer, the difference in our ages had become more conspicuous, and the dynamic in our relationship followed suit. That summer, he was more interested in girls than in games, but I had yet to make such a transition.

One day during his visit, we took a bus ride during which he chatted up a couple of girls while I sat awkwardly by his side. To my discomfort, a plan was made to meet up with them again after dinner. I was very nervous but also determined to follow Michael’s lead.

After we’d eaten, he suggested that we change clothes for the scheduled rendezvous. I wasn’t sure why that was necessary but decided to go along. Once the bedroom door was closed for privacy, he looked at me quite matter-of-factly and spoke these indelicate – and, ultimately, indelible – words.

“Your legs are really ugly. You should never wear shorts.”

Michael honestly cared about me and was not at all trying to be mean. Rather, in a big-brotherly way, he was trying to help me be more attractive to girls by encouraging me to hide one of my least attractive features. His concern wasn’t handled in the most sensitive of ways, but I’m certain it was well-intentioned.

Of course, I looked down at my legs, which I’d never really thought much about before, and I saw that they were indeed thin and bowed. I would never again be free of that awareness, which quickly morphed into shame. I peeled off the shorts I’d been wearing and pulled on a pair of bell bottom jeans.

“Much better,” he affirmed.

—

When I learned of Michael’s death, amidst the many memories, his “counsel” echoed loudly in my mind.

More than 50 years later, I still find even the thought of wearing short pants deeply disquieting.

—

I had crushes but never dated in high school. And, on the night of my senior prom, I went bowling. I had asked a young woman to be my prom date, but she politely declined. I simply couldn’t muster the courage to try again.

When my friends Rick and Pat picked me up, it was just getting dark. Enroute, we passed a couple of limousines, likely filled with some of my classmates. I crouched down in the seat and turned my face away from the window.

Pat must have noticed. “Are you okay?” he asked.

Unable to hide my embarrassment, I confessed that the prom was that evening, and I was not going.

Both were respectfully quiet for a few moments. Then, with a smile on his face, Rick blurted, “How about a dollar a string and a nickel a point?” A modest gamble always enhanced the experience for him.

“Works for me,” I responded, and we drove on.

I lost that night – twice, in fact, if you count the bowling, but my supportive friends softened the blow.

—

For much of my adolescence, I was wracked with shame and self-doubt. I had good friends, but love seemed unreachable or, at best, unsustainable. Then came Marianne.

—

I’ve never been much of a party person, even during my college years; so, choosing to attend the English Society’s end-of-semester gathering was a bit out of character. It helped, of course, that my friends Jimmy and Mike would also be there.

Wine in hand, the three of us were clustered together talking when a beautiful, unfamiliar young woman approached our group.

“Is this where the upperclassmen hang out?” she asked with a sweet smile. I was mesmerized.

These days, when recalling that moment, Marianne will say that she wondered why this guy’s eyes were so wide and staring. I wasn’t even aware of it at the time.

While the notion is very romantic, this was not an experience of love at first sight, though love would easily follow. Rather, and this is so difficult to explain, I knew at that moment, with a mysterious certainty, that I was staring at my future. The experience was like a stirring deep in my mind or heart or both that overwhelmed me.

If a brief conversation followed, I have no recollection of what was said. I’m not sure that I spoke at all, and I didn’t even get her name.

The party – and, with it, the academic year – ended, the crowd dispersed, and a long Marianne-less summer began. It would be my last such summer. In the ensuing months, I suspect my friends grew weary of my frequently expressed preoccupation.

“I know her,” my friend Jerry said at one point. “Her name is Marianne Auclair. She’s the friend of my friend Chris, and I’ll introduce you this fall.” His promise both terrified and thrilled me.

Eventually, September arrived. Unbeknownst to me, Jerry and Chris had worked out a plan to bring Marianne and me together. On the first day of classes, Jerry and I were walking together when we saw Chris and Marianne approaching from the opposite direction. My initial excitement quickly yielded to fear.

“Hey, look who’s coming,” said Jerry. “This is it!”

“No Jerry,” I countered in a panic. “I’m not ready!”

“Oh yes you are,” said Jerry. And there was no escape.

The introduction happened. I told Marianne that I remembered her from the party in the spring and asked if she’d had a nice summer. We talked a bit about the classes we were taking that semester, and said that maybe our paths would cross again soon. With that, we parted company.

“Was that okay? Did I seem overly anxious? Did I make a fool of myself?”

Jerry laughed and assured me that things had gone really well. “Now the ice is broken,” he said. “It will be easier next time.”

One of us suggested getting something to eat. We weighed our options and decided on Engine House, a pizza and sandwich place about a mile from the campus. Owing to the distance, the restaurant was not a typical college hotspot. When we got there, in fact, it was nearly empty, and we were the only obvious college students present.

We placed an order and then waited by the counter for our food. After a few minutes, a bus pulled up to the corner just outside, and two people got off. One was a young woman I did not yet know. Astoundingly, the other was my future.

When they came inside, I was beyond exhilarated. While I’d been terribly nervous during our introduction just a short time earlier, I now had a sudden surge of conviction that her presence at Engine House was no coincidence. I had to act.

As I walked over to greet them, I noticed a puzzled expression on Marianne’s face.

“I didn’t expect to see you here,” she said. Then, turning quickly to her companion, “Lisa, this is Steve. Steve, this is my roommate, Lisa.”

Lisa and I exchanged pleasantries, then I pivoted and looked directly into Marianne’s captivating eyes.

<Deep breath!>

“I can’t believe we’re both here,” I marveled, “but this gives me an opportunity to ask you an important question. Could I take you out to dinner on Saturday?”

She thought for a tortuous moment, and then said, “Well, how about if I make you dinner instead?”

We dined together for the first time on Saturday, September 13, 1980. She made me a tomato and cheese casserole, which is now one of my favorite dishes. We’ve been an exclusive couple ever since.

—

There is a story I like to tell that, I believe, demonstrates the blessing this woman, this gift of God, has been to my life. Its simplicity is its depth.

During the work week, I’m typically up by 3:00 a.m. because I find early morning to be the best time to pray. Fortunately, Marianne is a deep sleeper, so she seldom stirs as I stumble from the bedroom.

These days, I delay breakfast until I arrive at work several hours later, but in the past it was my routine to start the day with a piece of fruit (usually an orange), an ounce of mixed nuts, and a cup of black coffee.

Since my teeth are quite sensitive to cold, I would take an orange out of the fridge and put it on the kitchen counter before going to bed. One night, I forgot to do so; and, when I woke up in the morning, one of the first thoughts that crossed my mind was that I’d be eating a cold orange that day. When I got to the kitchen, however, there was my orange sitting on the counter.

Marianne!

I know it may sound like a small thing, but my life is brimming with such routine acts of loving kindness.

—

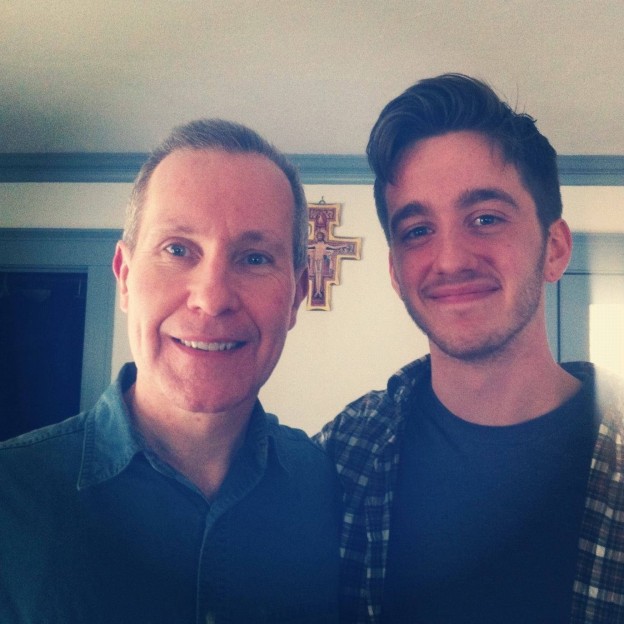

Marianne and I have been married for nearly 42 years. She is still my future, but she is also the central figure in a very rich past. We are blessed with children (3) and grandchildren (9), who are the beautiful fruit of our love.

And, guess what! My bride loves my legs. She has seen them, stroked them, massaged them, and even kissed them countless times. In her presence, shame evaporates.

—

“How about a dollar a string and a nickel a point?”

“Thanks, but not tonight, Rick. I’ve got a standing date… and I just might wear shorts.”