The memory is vague, almost dream-like. My paternal grandfather, who died in 1960 when I was still a toddler, is atop a fight of stairs in the family home and speaking with my father, who is with me at the bottom of the stairs. I can’t describe my Grandpa’s features except to say that he was an old man, nor can I recall anything distinctive about his voice or manner. To be honest, I’m not even sure that I can trust my recollection at all. I know, it’s not much to go on; but, somehow, it’s proven to be enough. That one obscure memory has always served as my relational touchstone with my father’s father, a foundation upon which to build.

For most of my life, I had no such connection with my maternal grandfather.

—

During the opening credits of Rocky Balboa, the 2006 entry in the “Rocky” film series, there is a touching scene wherein the aging title character visits the gravesite of his beloved wife, Adrian. While brother-in-law Pauly awkwardly watches and waits, Rocky sits on a folding chair in quiet communion with his departed bride.

When he’s ready to leave, Rocky tenderly kisses the top of the headstone as if it were Adrian’s soft, blushing cheek. Then, he collapses his chair and returns it to its storage place in the sturdy branches of a nearby tree. The message is clear. Rocky visits often; and, the audience feels the good man’s pain.

Intentionally or not, this scene models behavior that contemporary grief counselors might describe as an “enduring bond,” i.e., a psychological and/or spiritual relationship that continues even beyond death.

While love is typically the defining characteristic of such bonds, other sentiments can certainly be involved as well. It is not unusual, for example, for someone to come to a gravesite bearing unresolved anger, regrets, a desire for forgiveness and reconciliation, or countless other all-too-human emotions.

Indeed, graves can be complicated places.

Perhaps that explains, at least in part, why I seldom visit graves, even of people I’ve dearly loved. Knowledge that the bodily remains (the “earthen vessel”) of a loved one lie beneath my feet affords me neither inspiration nor consolation. By faith, I believe the person I cared for is no longer there. Rather, she/he is now in the hands of a loving God. That considered, I’m far more likely to work on my “enduring bonds” behind closed doors during prayer. It is there, rather than in the cemetery, where I’ve had some of my most satisfying “conversations” with departed relatives and friends.

There is, however, one grave that tugs at my heart like no other.

—

John J. Christopher, my mother’s “Papa,” died when he was only 58 years old in 1944, a terrible year for the family. I have shared previously about how little I know of my grandfather’s life and death. In fact, as I write these words, it occurs to me how few photographs I have seen of him, perhaps just one or two.

Whenever I would question my Mom about my grandfather, she’d always seem hesitant to speak. Was it grief or something else that knotted her tongue? Judging by the sensitive tone her voice assumed whenever she did speak of him, it was clear that her Papa held a special – albeit, a hidden – place in her heart.

Many times, I’ve found myself pondering unanswered questions in front of my grandfather’s grave, a resting place he shares with his oldest child, Mary, my aunt, who pre-deceased him during that fateful year of 1944.

So, who was this man? What were his treasures? Did he believe in God? Did he make friends easily? What made him smile, laugh, cry? Did he have a hobby? What burdens did he carry? What were his gifts? His regrets? His foibles? Did he pray? Was he a dreamer? What were his politics? Was he satisfied with his life? Was my grandmother his first love? His true love? If so, did he love her to the end? Was he always faithful? What thoughts filled his mind in quiet moments… and, in his final moments? What were his fears? His temptations? Who were his heroes? How did he die? And, more importantly, what guided how he lived?

My Mom was the last surviving member of her first family. When she passed in March of 2015, it meant that all those who had been closest to my grandfather were now gone. So too, I imagined, was any hope I had of finding answers to my myriad questions concerning this stranger whose blood I share.

—

While going through my Mom’s things shortly after her death, my wife Marianne and I came upon a diary my Mom had kept in 1940 when she was 13 years old. I’d never known of the diary’s existence and couldn’t resist immediately exploring it’s pages, which were a genuine revelation to me. Marianne, ever-gracious (and knowing me only too well), gave me a pass on further sorting that day.

Just holding the book stirred my emotions. Seventy-five years earlier, my Mom had recorded the highlights of her adolescent life in its pages, beginning each entry with “Dear Diary” and concluding with “Love Eleanor.”

The textured cover of the book bore the words National Surety Corporation 1940, and the title page read National Surety Diary 1940. A handwritten note on that title page explained that the diary had been: “Given to me from Johnny as a Christmas present.” Johnny was my Mom’s older (and only) brother. Just a few years later, in 1944, he would be horribly wounded by a German soldier during ground fighting in Sicily. He’d be in recovery for a long time, but he’d live and eventually return home.

My Mom wrote faithfully in her diary through May 27th of 1940. Then, for whatever reason, her daily entries abruptly ceased. Mostly blank pages followed; however, there were a handful of later entries, including a few dating from 1949 and 1951.

There were many gems to discover in the diary’s pages, including my Mom’s first (recorded) encounter with my father on Thursday, May 2nd. That entry reads as follows: “Then Robert Dalton called me by my first name and then hit me over the head with a magazine. It seemed so nice.” Knowing the pain that awaited them later in life made this sweet passage particularly poignant for me.

I won’t delve into the specifics of my Mom’s early adolescence beyond these few observations. At age 13, she was a bit boy-crazy and seems to have prompted innocent flirtations (e.g., the magazine on the head, above) from more that a few young suitors. She struggled in a couple of her subjects at school, was somewhat fashion-conscious, and was prone to being “kicked out” of the public library. (Note: Her librarian son was aghast to learn this detail.) She and her older sister, Edna, were inseparable, but they also had strong arguments, a characteristic they would carry into old age. My Mom’s allowance at the time was $0.30/week, and she often used the money to go to the movies with her friends. She felt things deeply. In short, she was a typical teenage girl of her time.

As these previously unexplored aspects of my mother’s life unfolded with the turning of each cherished page, I was too taken with her story to anticipate what was coming; but, my Mom was about to introduce me to my grandfather.

—

Mystery sometimes begets romanticized notions; but, any idealized images I’d subconsciously formed about my grandfather were quickly humanized by my mother’s pen. In all, there were twelve entries in the diary that mentioned my grandfather. Some were just brief references, but a precious few were more revealing.

Rather than recount all of the details, I will instead summarize the still thin portrait of my grandfather that emerged for me from the diary. Some general aspects of his life, e.g., that he once worked for a railroad and that there was some tension between him and my grandmother, were not a total surprise. The insights I gleaned about his temperament and character, however, were altogether new and satisfying. I was also surprised and saddened by the intensity of the rift between my grandparents.

John J. Christopher was an emotional man whose identity was closely tied to his work. For twenty-five years, he was employed by the narrow gauge railroad that operated in his community. After experiencing a serious drop in ridership, the railroad shut down on January 27, 1940. My Mom’s diary entries on that fateful day and the next both speak of her Papa’s constant tears at the loss of his job. “He cried into five hankies. Ah diary, it was so sad.” At one point, she also recounts him calling out hysterically: “It’s gone!” His children gathered around to console him in his grief. That was very heartening to read.

My grandfather seems to have had a strong sense of responsibility regarding his family. As much as the job loss devastated him, he was quick to search out employment and apparently found a new position in less than two months. My mother mentions both a new job and the start date, but she provides no further details about either the employer or her father’s adjustment to his new work.

As mentioned, the relationship between my grandparents was strained, perhaps torturously so. Six of the twelve diary entries that mention my grandfather reference either their fights or their complete lack of communication. No motive for their discord is ever mentioned, but the impact upon my Mom and her siblings appears to have been quite severe. At one point, my Mom reports that her oldest sisters, Mary and Barbara, had devised a plan to save their money and move out of the house with all three of their younger siblings (Johnny, Edna, and my mother) due to the fighting. That plan, at least during the period covered by the diary, was never carried out.

Alcohol is mentioned in passing once, but the reference, as I see it, is open to interpretation. Exactly one week after the traumatic loss of his railroad job, my Mom wrote: “Papa is very good lately. Hasn’t drank any liquor. He used to all the time.” Can her last sentence be taken literally, or did she mean “all the time…” since losing his job? I will likely never know.

Finally, despite the stress in his marriage and his devastating work situation, my grandfather appears to have had a strong relationship with his children. As noted, they gathered around to console him after his job loss. Also, when my Mom was laid up for two weeks with a terrible sore throat, she wrote of how kind he was to her during the illness. And, he apparently tried to involve his children in activities around their home. My Mom reports affectionately, for example, about spending a Saturday morning painting woodwork with her Papa.

This last point evokes a beautiful picture in my mind, a picture that, like the image of my paternal grandfather atop the stairs, can serve as a foundation for an “enduring bond.”

—

My Mom’s diary doesn’t come close to answering all of my questions about my grandfather. Still, it provides marvelous insights I’d never had before about both him and my mother herself. I consider it one final, loving gift passed from mother to son.

I only wish she’d written much more.

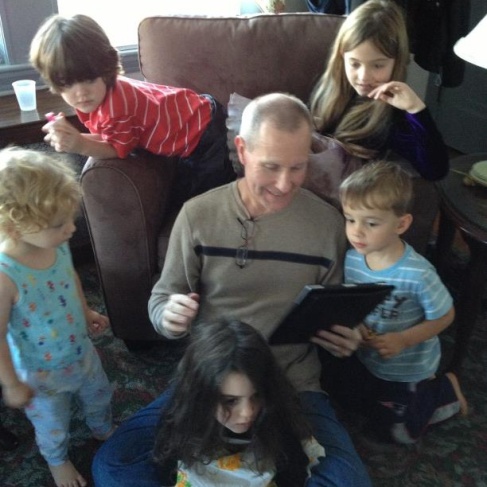

P.S. Writing is difficult. One reason I take up the pen (or, the keyboard) is to provide future generations in my family with an understanding of who I was and what I valued. Perhaps it won’t matter to anyone. Then again, if one of my grandparents or great-grandparents had shared something of her/his heart in writing, I would treasure it beyond measure. By the way, I also hope that my experiences might strike a familiar chord within you and somehow prove to be a blessing in your life.